The ABC of Trust

Kim Dalton

9 May 2017

The ABC is one of Australia’s most trusted public institutions. It is generally considered to be one of Australia’s most important cultural institutions. The ABC’s brand is arguably part of the nation’s identity. However, can the ABC really be trusted with the future of Australian children’s television?

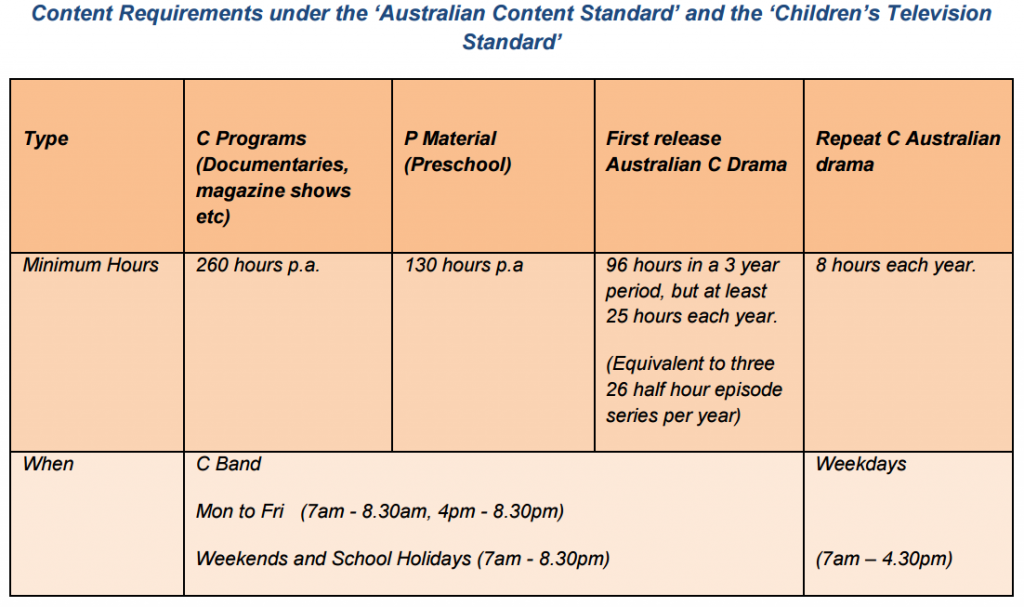

For Australia’s commercial free-to-air networks 7, 9 and 10, The Children’s Television Standards (CTS) mandate minimum levels of children’s (C) drama and pre-school (P) programming to be broadcast each year. For over 30 years, the networks have complied with the obligations of the CTS, although arguably they have never fully embraced the intent or spirit of them. From their perspective, the cost of commissioning and acquiring children’s programmes together with the opportunity cost associated with restrictions around programming and advertising results in a net loss in these areas of their schedules. Reducing, abolishing or in some way amending the CTS has long been a reform objective.

Politics are always present in any area of media regulation, and maintaining a strong antisiphoning regime, reducing licence fees, and changes to the reach and cross-media ownership rules are much higher priority issues for the networks than the CTS. If political capital is to be risked or expended, children’s content regulations have not been an issue of the first order. However, if all or most of these bigger issues are dealt with by the government and parliament in the first part of 2017, the CTS are likely to move up the networks’ reform agenda.

The networks argue that the television environment has changed significantly since the CTS were first developed in the late 1970s. The ABC now provides two dedicated children’s channels as well as a comprehensive on-demand service. Global brand children’s channels are available on pay TV as well as new web-based or online on-demand children’s services, all of which are available across multiple platforms and on multiple devices. Children’s programming blocks on otherwise general programming, linear broadcast channels cannot compete. As a result, audience numbers are falling.

The Australian Children’s Television Foundation (ACTF) and children’s television producers argue that a significant children’s audience is not served by the various subscription, online or on demand services. Furthermore, children’s access to Australian stories and Australian voices is a fundamental social and cultural issue. When offered the choice, children want to watch Australian programmes, but they can only do so if the programmes are produced and are readily accessible. The CTS also created demand for Australian children’s drama and animation content, contributing to the development of a significant and successful Australian children’s television production sector.

How this argument will resolve is uncertain. However, the networks are a formidable lobby group and with a government, and a prime minister in particular, receptive to arguments about old world regulation no longer working in the new and open digital media environment, some form of change is likely. At the same time, no one wants to say that Australian children should not be able to grow up hearing their own stories and their own voices. Various modifications and solutions will be canvassed but one that is beginning to get some traction is that perhaps the ABC could step into the breach and become the provider of Australian children’s content.

There are immediate and obvious concerns about this proposal, not least that a single provider and a single gatekeeper is never healthy, particularly in an area where many of the decisions are subjective, are about taste and standards, and require creative judgement. Funding of an expanded service is also an issue. The ABC has indicated an openness to the proposal but, quite rightly, has been quick to say that it must be funded. The elephant in the room, however, is the question of whether or not the ABC can be trusted with this responsibility. History, and especially the ABC’s track record in the last few years, would suggest that it cannot.

In its triennial funding budget of 2009, the ABC received an additional and specific allocation in order to expand its children’s offering. This allocation rose over 3 years to AUD$27 million a year and remained at that level as part of base and indexed funding. The ABC had promised the government, the ACTF – its partner in a very public funding campaign – the production industry and ultimately its audiences a dedicated channel for school-age children, with a comprehensive offering across all programme genres and with an Australian content level of 50%.

Within 3 years, the ABC was delivering on its 50% Australian content promise on the new ABC3. Importantly, it was delivering to Australian children a diverse programme offering across live action drama, animation, comedy, reality, entertainment and factual. The ABC also set out to increase the breadth and depth of the children’s production sector. It did this by discovering and developing new on-screen and off-screen talent and by attracting existing senior producers, writers and directors working in adult television into the children’s area. Audiences responded very positively. By 2013–2014, among 5- to 12-year-olds, the ABC’s reach was 43.6% and its daytime share was 30%.

Series 2 of the award-winning ABC3 program Bushwhacked! aired in March 2014

Unfortunately, just a few years later, it is beginning to look like a golden era that was all too soon over. Notwithstanding the very specific allocation of funds, within less than 4 years, the ABC was reallocating these funds. The ABC’s children’s budget has been reduced by 50% or more than AUD$20 million, an amount that is disproportionate to any cut it has received from the government. The ABC has also quietly halved its Australian content objective from 50% to 25%. Importantly, the reallocation of funds actually began before the Abbot/Turnbull cuts took effect; it continues with further and ongoing cuts to the children’s budget.

The reality is that the ABC has over the years demonstrated that it does not have a commitment to its children’s services or programming. It is not obliged through its Charter to properly serve younger audiences and sits outside the framework which governs children’s television on the commercial free-to-air networks. Hence, there are no requirements for minimum levels of Australian content on its children’s channels, nor are there any definitions of children’s content or Australian programme more broadly that apply to the ABC.

Ultimately, this is an issue of governance, the implementation of public policy and the national broadcaster. The debate that will occur next year around the CTS will be one of public policy. Should Australian children have access to Australian stories and Australian voices? If so, what are the mechanisms and processes which will deliver on public policy objectives? The solution, at least in part, should involve the ABC. However, the ABC’s governance and its relationship to government public policy objectives will need to be addressed.

The children’s television production sector, the networks, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA), Screen Australia, the government and perhaps even the ABC itself will need to address this issue. Clear outcomes and objectives will need to be set in terms of overall levels of Australian content, levels of Australian C drama in particular and diversity of genres more generally. Agreed definitions and what qualifies as Australian and children’s programmes will have to be established. Most importantly, the integrity of funds allocated for children’s programmes and services must be assured. The ABC cannot agree, as it just has, to certain objectives, seek and receive additional funds, and then reallocate them with no discussion or consultation and with no transparency.

The ABC will object to any imposition of government policy objectives or outcomes on its operations and services as it has throughout its history. It will claim this is an assault on its independence. Recent history clearly demonstrates, however, that the ABC cannot be trusted to honour its commitments to Australian children’s content or to its children’s audiences. Its independence will be used as a shield to allow it to allocate resources according to internal priorities with no public scrutiny and with no regard to broader public policy settings.

This piece was originally published in the May 2017 issue of Media International Australia.

Kim Dalton discusses the ABC and Australia’s screen culture further in his newly released essay for Currency House.

Comments

Comments for this post are open.