The Storyteller, by Tony Morphett

ACTF

7 Jun 2018

This editorial was originally published in the Annual Report 1988-89 of the Australian Children’s Television Foundation.

Tell me a story …

Well, once upon a time …

Storytelling is one of the oldest and one of the most common of all human traits.

It is also one of the strangest and one of the least understood.

The practice is so old, so common to all societies, that we do not see its strangeness.

But observe; a story is a lie; it is a series of events which have not happened, concerning a set of people who do not exist and indeed sometimes the people live and the events happen in places which do not exist.

And yet, people of every culture the world has ever known have told stories. The story is more common in human societies than the invention of the wheel, than the discovery of how to make fire. All people tell stories.

Why?

Well … they are a way of understanding our lives, are they not? A way of putting a pattern on events which otherwise seem mysterious and meaningless, a way of explaining drives as deep as our DNA or as shallow as this morning’s gossip.

They are a way of seeing our own society, and the place we have in it.

They are universal, in that they deal with the journey that all human beings go on, from birth, through the meeting of challenges, through victory and defeat, to the last great challenge of death itself.

They are particular, in that they let us hear these universal stories in the accents of our own country, town or village.

They are necessary to our understanding and to the health of our society.

Storytellers, the women and men who tell and retell universal stories in particular times and places sometimes go by other names.

Once they were bards, and now they are called novelists, or writers, or screenwriters or journalists or filmmakers. They are all storytellers.

The ancient stories – of birth, and mating and death; of the journey from the sunrise to the place of the setting sun; of the love that sends a lover down into the underworld to recapture life from the palace of death itself; of the hero called from obscurity to face tests and gain a boon for humankind – all these ancient stories must be told and retold every generation in the context of the tribe, in the language that the tribe can understand.

For example, the fable of Beauty and the Beast could be summed up as “a prince lives under an evil spell until a young girl enters his castle and delivers him from the spell through her innocence and love”.

But that is also the story of Charlotte Bronte’s novel Jane Eyre. It is also the story of Daphne DuMaurier’s novel Rebecca. It is also the basis of most of the popular Gothic romances. The story embodies an old truth – “love can heal” – but must be retold every generation in order to be fully understood.

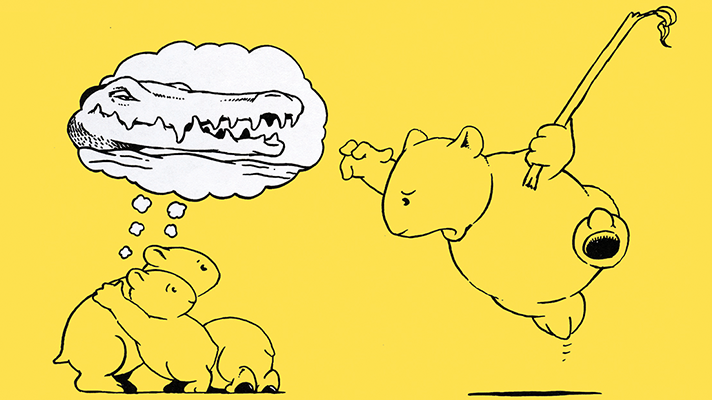

Another example, the film Jaws, might be summed up as “a monster threatens a village but is defeated by human courage”. It is also the story of the films Alien and its sequel Aliens. It is also the basis of all dragon stories, of the Perseus story, of several of the Hercules stories, and of Beowulf. But it is told and retold in all generations, all cultures.

It would seem that these stories are deeply embedded within us, virtually in our DNA, they are part of what makes us human. It is why we want to tell them and why we want to hear them again and again.

The storyteller’s job is to sit in the tribe, and spin these tales anew each generation. In the potent phrase of one of Australia’s preeminent modern storytellers, George Miller (the filmmaker who gave us Mad Max), storytellers are “servants of the collective unconscious”.

All cultures must retell these universal stories for themselves, they must explain them in their own terms … or cease to be cultures.

If you do not tell your own tribal stories, you become detribalised. The tribe does not own its dreams and dies as a tribe.

Cultural disaster. National disaster.

Because cultural integrity equals national integrity equals national survival.

White Australians should know all about this, because we have, sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously, done it to another people. The way to destroy a people is to detribalise them, and the way to do that is to take their stories and their dreams and replace them with your own. It is a most subtle, yet most common form of imperialism.

In the past small and weak cultures survived through isolation. That mechanism no longer exists.

In this part of the 20th century, the great storytelling medium is film, whether shown in cinemas, or on television sets either as broadcast or played from VCRs.

Because of this, and because of rapid transport and instantaneous communications from one side of the globe to another, we are at a branching of the paths.

One path leads to a multicultural planet, a sort of universal SBS where we can have our own cultures, and at the same time enjoy the richness and diversity of hundreds of others.

The other path leads towards sameness, uniformity, an acquiring of a dominant international culture probably based on the enormously energetic and powerful culture of present-day California.

This comment should not be read as anti-American. I am, if anything, pro-American culture. I enjoy American films.

But I also want to be able to make our own, see our own culture on the screen, hear our own accent coming from our own actor’s lips.

This will take struggle. It would make economic sense for all English-speaking film and television to be manufactured in Los Angeles, and for the rest of the English-speaking world to watch it.

This is not an unthinkable proposition. It has been thought in the past in various forms and will be thought again in the future.

Australia is an English-speaking country with a small population and therefore a small economic audience base. If we are to continue making our own films and television dramas in the face of competition from the two large English-speaking nations, we will need to continue to have Australian quotas for television programs, and some form of Government support for our film industry.

Without these two factors operating, we cannot maintain a big enough pool of talent to continue participating in the dominant storytelling medium of our time.

And if that happens, then your children will grow up detribalised, dreaming other nations’ dreams, being formed on other nations’ stories.

This century began with our ceasing to be a colony. It could end with our becoming a colony again, this time a cultural one.

Comments

Comments for this post are open.